To commemorate the centennial of the passage of the 19th Amendment, which gave women the vote, Vulcan Park and Museum created Right or Privilege? Alabama Women and the Vote. The exhibit was curated, researched, and written by Vulcan staff with graphic design by Mandalu Designs. The exhibit was created and is presented in partnership with several other civic and cultural organizations in Birmingham. More information about partners, programs, and visiting can be found on our website.

Going into this project, we knew we wanted to tell a women’s suffrage story and we knew it had to be bigger than just a focus on the years leading up to the 1920 passage of the 19th Amendment. It couldn’t end in 1920, because the 19th Amendment didn’t actually enfranchise most women in Alabama in 1920. State laws, in defiance of the US Constitution, kept most black women and poor white women from voting in Alabama until the Civil Rights Act of 1965 was passed by Congress. We thought it was important to tell the story of all the women who had to fight after they should have been constitutionally able to exercise their rights. We also wanted to tell stories that most people didn’t already know.

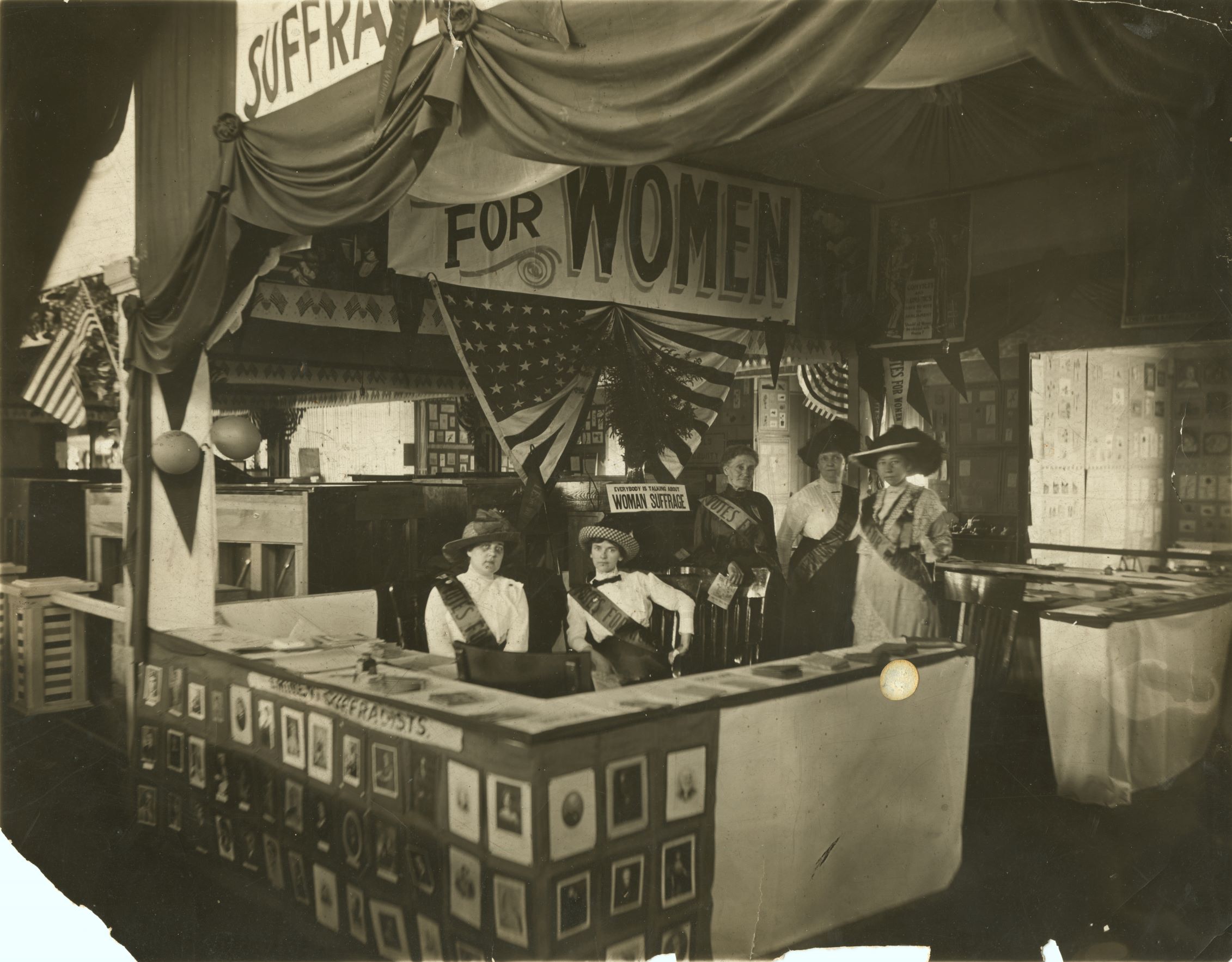

Women’s suffrage booth at state fair, Birmingham, Alabama, 1914. Pattie Ruffner Jacobs is seated on the left. Alabama Department of Archives and History.

Early on, several goals for the exhibit were identified broadly by Vulcan staff, stakeholders, and community partners:

- Examine the specific challenges faced by suffragists in Birmingham, Alabama, and the South

- Examine the underlying racial issues that caused the women’s suffrage movement to be effectively a white movement in the South

- Uncover through research and tell the story of grassroots voter registration and activism efforts by women during the 20th century through the Civil Rights Movement

- Instill in visitors a sense that they should use and value the right to vote that was so hard fought and that so many people now take for granted

- Tie this history to current events: increased number of women running for office; threats to voting rights in US and AL; current work to establish and maintain voting rights here and abroad.

- Tell an inclusive story that will engage a wide audience

To meet these goals, this exhibit would have to talk about well over 100 years of history. The gallery which would showcase this history is about 200 square feet.

How do you tell such a big story in such a small space?

We started by defining our big idea. The big idea is what a visitor’s takeaway from the exhibit should be. Ours was: Women are changemakers and your vote matters

Next, we defined a scope for our story to set boundaries about what we would cover.

- We would focus on women specifically

- We would focus on Alabama with a preference for Birmingham stories (because that’s where we are located and where a majority of our visitors live)

- We would focus on women’s work on voting rights until and beyond 1920 into the present day.

Marchers on Dexter Avenue in Montgomery, Alabama, approaching the Capitol at the conclusion of the Selma to Montgomery March, March 25, 1963. Alabama Department of Archives and History. Donated by Alabama Media Group. Photo by Tom Self, Birmingham News.

With this boundary in place, we delved into historical research and spent hours and hours with books, scholarly journals and archival collections. We collected reams of information.

Armed with a general scope for the exhibit and our newfound knowledge, it was now time to develop a thematic structure that worked with the content to communicate the key ideas. We decided we would use standalone four-sided columns to provide “Focus Stories” on individual women in the center of the gallery. Information, photos and artifacts providing the historical context of their work and time periods would be presented chronologically along the gallery walls.

Curating an exhibit is about making choices. Curators choose what to present and how to present it. Some of the choices we made were:

An explicit focus on women. Although many men did important work in voting rights, we chose to highlight women who have been historically overlooked because the 2020 centennial is a milestone in women’s rights. And we wanted to tell stories most people were unfamiliar with.

Which women to feature. We were careful to highlight women from a variety of movements and backgrounds to show that the fight for voting rights was much more complex than just the 19th Amendment’s ratification. We wanted to highlight women who made a real impact and sparked real change and tell stories the public had not seen before. If there were several potential women we could include, because of the nature of exhibits, often the women who had the best documentation of what they did, women I could find photographs for, or women who had the most unique stories would end up being selected.

Where the women were from or where they were active. We prioritized women from Birmingham who had compelling stories over women from other cities because we are in Birmingham and so is much of our targeted visitor base. Other cities are also doing their own suffrage commemorations and exhibits, so women from those cities were likely to be featured there. Some women from other cities were too important not to mention though.

The historical times covered. The exhibit covers such a long time because we thought it was important to really dive into the racial issues that have always been enmeshed with voting rights in Alabama. We want to provide a historical context for how the vote was historically denied to black people and that really dates back to slavery, the Civil War, and Reconstruction. Likewise, because of the racist and segregated legal legacies of those times, the 19th amendment did not actually enfranchise all women in Alabama. Only an elite white few – like the male electorate at the time. The vote was not significantly extended for African Americans until the voting rights act of 1965. And racial issues still impact discussions over voter rights and access to this day.

Woman registering to vote with federal examiners in at the Fort Charles Henderson armory in Troy, Alabama, 1966. Alabama Department of Archives and History.

Tying historical content to the present day. Including information about women’s political participation since 1920 helps to reinforce the idea that women were and are political changemakers. It also shows that women benefited from the efforts of those before them. Talking about who votes today ties the past to the present. Including a call to action, hopefully, inspires a visitor to register to vote and use their vote.

Sometimes decisions are shaped by reality.

Few people came forward with artifacts, and few repositories had artifacts we could borrow. That meant our exhibit would have to rely more on historic photographs than artifacts. The square footage of the gallery can also be limiting. Big artifacts won’t fit in there, and only a few artifact cases will.

Sometimes we couldn’t find photographs of women who had awesome stories. Without a good visual, people typically won’t come read what’s written in an exhibit. So, we had to choose stories which had good visual elements to accompany them.

Sometimes the sources we expected to provide great information or photographs did not actually have that information. If a story couldn’t be vetted and verified through research, we couldn’t use it.

The format of an exhibit can also limit you. We selected four-sided columns that could later travel to other venues as the format for our focus stories about individual women. That meant we could feature four women around four different themes: Early days of women organizing, the women’s suffrage movement, women’s activism between 1920 and the Civil Rights Movement, and the Civil Rights Movement. We have four of those columns because of square footage in the gallery. Women profiled for their political participation are featured in the chronological presentation on the gallery walls.

The interior of Linn-Henley Gallery with the suffrage exhibit installed.

Sometimes decisions are shaped by opportunity.

Over the course of the research process we worked closely with the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute to study their oral history collection and to secure loaned artifacts for the exhibit. Concurrently, they were working on digitizing their oral history collection and launching a new website where the public could access it. This exhibit provided a wonderful opportunity for us to partner on an oral history feature in the exhibit that would tie to their new online platform. With the exhibit opening, the BCRI officially launched their new oral history site. As a result, more people came to the exhibit and more people visited the website.

Sometimes decisions are shaped by budget.

We planned to have an interactive element in the exhibit to illustrate to visitors the barriers that many people faced when they tried to exercise their voting rights. The grant we anticipated to use to fund that piece was not a large enough amount, so we were not able to do it.

All of these decisions and factors shaped the final exhibit that was installed in our Linn- Henley gallery in January. Were our decisions successful? Right or Privilege will be open through January 3, 2021. We hope to be back open soon so you can come see for yourself!

If you’d like another behind the scenes look at the exhibit development and design process, visit our friends at Backstory Educational Media to learn how they created Terminal Station: Journey to the Great Temple of Travel for exhibition in Vulcan’s Linn Henley Gallery last year.

Jennifer Watts is the Director of Museum Programs at VPM, which means that she oversees both the museum collection and all things educational. In her spare time she likes getting outdoors, enjoying the arts, and spending time with her family.